How to crack the Voynich code, and how not to…..

Here is a pastiche of the type of message I get almost every week:

“Dear Mr Bax,

I am writing to tell you that I saw your website and I have deciphered the Voynich manuscript. You won’t believe me but it took me only two hours! I haven’t read anything much about the manuscript, but I am 100% sure that it is written in Icelandic/Hottentot/Mayan/Greek. Personally, I don’t know anything of that language but I put some words into Google Translate and it came out with this text:

…….. Â What do you think?”

Since I get these messages so regularly I thought it might be useful to sketch out why this approach to the script and language of the Voynich Manuscript (VM) is so wrong-headed, and so unlikely to lead to a successful decoding. Â I will then to set out what I see as a potentially more fruitful, though far more difficult, direction.

Let’s return to my composite email above. Believe me that I am not exaggerating when I say that that all elements of it occur repeatedly in many messages I receive. Some of them are obviously foolish – for example, no-one should be so arrogant as to work on the manuscript without at least doing some basic research into what others have tried to do for many years, starting with René Zandbergen’s site.

However, the aspect which I want to discuss here, and to discourage as strongly as I can, is what I will call the ‘word-by-word‘ approach Iron Door Download. This means looking at each word of the manuscript, trying to spot a resemblance in another language (say Greek) Â then moving to the next word and finding another word in Greek which might fit, and so on. Â Often this is done with the help of Google Translate, by putting in the words one by one, or even together.

An example of this approach is the work of Maurice and Anita Israel which you can find here, which claims that the manuscript is written in Greek. The authors kindly corresponded with me a while ago and set out their methods, which involve a letter-by-letter then word-by-word match of the type I describe above. Unfortunately, I’m very sorry to say that the results are unintelligible, and the authors admit that they have no knowledge of Greek at all. However, these authors are by no means alone –  we have seen other attempts to work word-by-word in a similar way. A common variant is to try to find anagrams to make the words fit better (see the ideas of Tom O’Neil here for example), which seem to me equally fruitless.

I know it is perhaps bad manners on my part to cite their work. After all, they are working hard and sincerely like everyone else to crack the code. However, I feel it is important at the same time to discuss different methods so as to help us to move towards a solution, so apologies to them if they disagree pc 바둑 게임 다운로드.

But why is this not a good strategy?

Why the word-by-word approach is not a good one

The reason why I feel that this approach is fruitless and (sorry to be so direct) a complete waste of time and energy, is because it fails to take account of some crucial elements of language, namely grammar and syntax. Dictionaries tend to give the ‘base words’ of a language, i.e. without any grammatical inflections. So for example a Latin dictionary will give you the base form for ‘girl’ as “puella”. However, it will not usually tell you that the other forms of the word, depending on the context, could be:

| Nominative | puella | puellae |

| Accusative | puellam | puellas |

| Dative | puellae | puellis |

| Genitive | puellae | puellarum |

| Ablative | puella | puellis |

(See here for discussion of Latin declensions)

In other words, the ‘word-by-word’ approach fails to take account of grammatical endings (for example case endings). So if you wanted to investigate whether the Voynich language is Latin, it would be foolish to take each word one by one, look them up in a dictionary (and even treat then as anagrams), unless you could also show that the words you see in the manuscript also match the expected grammatical case endings as well.

For example, if you want to show that it is Latin, you would need to demonstrate that a word which you think says ‘girl’ has the shape ‘puella‘ when it is the subject of the sentence (nominative), but the shape ‘puellam’ when it is the object (accusative). In other words, you could not claim that the language is Latin (or any other) until you can give us not only evidence about the word, but also evidence about the grammar of the language you are linking it with. No-one has successfully done this yet.

I have so far been talking about those grammatical elements which in many languages form part of the word (e.g Free download. case endings) but we also need to take account of syntax (in simple terms the sequence of words in the language). In many languages the grammatical elements work together with the syntax in interesting ways. For example, in Latin a preposition (such as ‘in’) is typically followed by the noun in the accusative or ablative case. So if you want to argue that the Voynich is in Latin, you should be able to identify prepositions and then show us that the following word is a noun in one of those cases.

My point here is to argue that a simple word-by-word approach is doomed to failure UNLESS it takes account of the grammar and syntax as well. Sadly, I have never seen a proposed decoding of the VM which even tries to do this.

(I could put this another way and say please do not send me any proposed translations which fail to take account of grammar! 🙂 )

A better way?

This brings me to the more positive part of the post, namely how I feel we could make progress on decoding the manuscript.

What I said above does not mean we shouldn’t work on the sounds and words of the manuscript. We should of course continue to work on trying to identify possible sound-letter correspondences Three Armed Forces War 3. and also words as best we can. Â But what we should also be doing is working on identifying grammatical and syntactical elements which might give us clues as to the underlying language. These might be case endings, for example, so we might find that a word occurs with different endings in different positions. Or we could try to identify particular word sequences which might be syntactic clues.

Let me offer three examples of what I see as possible grammatical/syntactic elements in the Voynich manuscript, to illustrate the kind of direction which, although it is far more difficult, might be more fruitful in the longer run than a word-by-word approach.

1. Grammatical elements – a possible conjunction

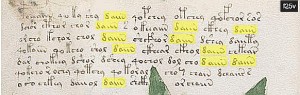

My first extended discussion  of the Voynich manuscript explored the possibility that the most common word in the manuscript, namely the word transcribed in EVA as ‘d a ii n’ might be a conjunction meaning something like ‘and’. Here is the word highlighted in folio 25v:

I revisited this argument in a post which you can find here.

I have suggested that this word could be read as something like ‘taur’ or ‘daur’ or ‘thaur’ (and see Derek Vogt’s transcription system here).  Since then, I have been on the lookout for languages which might use such a word as a conjunction. A few months ago I came across an interesting possibility, namely the Romani language, i.e Naver tv cast. the language of the Roma or Gypsies (not to be confused with Romanian). You can find an authoritative site about the language here.

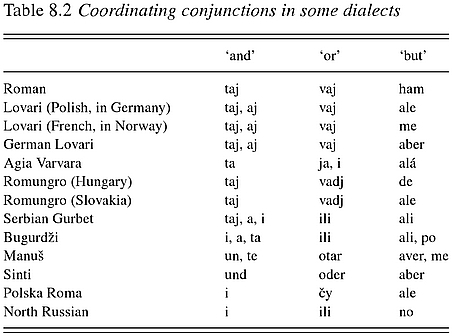

Many people have suggested Romani as the language of the Voynich, on various other grounds, including Derek Vogt on this site. Like Derek, I am especially interested  in the linguistic dimensions. In this light we can see that several dialects of Romani have a conjunction which is not dissimilar to ‘taur’, as you can see from this table from Yaron Matras’ book:

Matras, Y. (2002) Romani A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press (p201)

Matras also mentions variants such as ta / taj / thaj / te.  Now, this might not seem particularly close to ‘taur’, but we should not dismiss a connection too quickly, since there are many dialects of Romani with a lot of variation, and many changes could have occurred since the 15th century when the VM was probably written.

I was interested when Marco Ponzi independently noted the resemblance in his comment here, also discussed in Derek’s reply here. This does not in itself mean that we are correct, of course, but it is at least encouraging that others see similar connections.

2 Skyrim Launcher 다운로드. The definite article

A second element, and one which attracted my attention when I first looked at to the VM, is the frequent occurrence at the beginning of words of what looks like the Arabic attached definite article “al-“.  This feature is common in the Voynich star names (see e.g. here) where they could well be derived from Arabic names (such as ‘The bear’, ‘The serpent’ and so on).

What is odd about the cluster at the start of many Voynich words, however, is that they show more variation that (say) the Arabic definite article, sometimes apparently realised as EVA:o, and in other places as EVA:ok, EVA:ol and EVA:of. You can see possible examples here:

http://www.voynichese.com/#/exa:ok-

http://www.voynichese.com/#/exa:ot-

http://www.voynichese.com/#/exa:of-

If we are looking at a definite article, why would it vary from word to word? That is something which has never been satisfactorily explained, and has led many to doubt that they are definite articles at all.

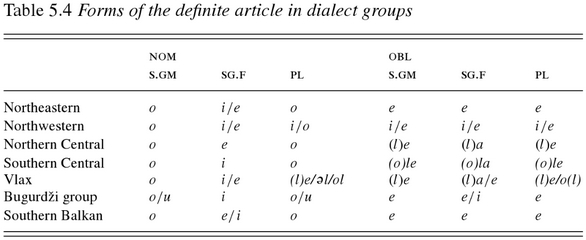

However, I recently noticed that again Romani has just such an odd feature, namely it has a definite article which comes before the noun (i.e. it is preposed), which looks in places rather like the Voynich particles, and which varies depending on aspects of the noun with which it is associated – with respect to gender, number and case.  See this table, again from Matras:

Matras, Y YouTube vr. (2002) Romani A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, p97

Again, we need to remember the passage of time between these modern dialects and the Voynich manuscript, but the point is that Romani definite articles vary in unusual ways just as the (possible) Voynich definite articles appear to do. It is possible that this could help to explain the variety in (what look like) Voynich definite articles.  Most of the variation in the table above has to do with vowels and with /l/, but Matras also mentions a Romani indefinite article ‘ek’ which could also come into the picture (ibid p98).

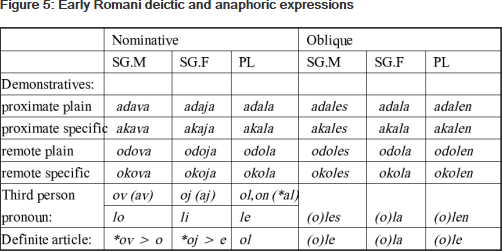

In addition, the comprehensive Romani website at Manchester University  offers an interesting list of “Early Romani deictic and anaphoric expressions”. The authors note that (as in other languages) the definite article might ultimately be derived from these demonstratives, a link which Matras also highlights (2002:111), so it is interesting to see  ‘vowel + k’ and ‘vowel + l’ in these too:

http://romani.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/whatis/structure/nominals.shtml

In  summary, this shows that if the elements in the VM which look as if they might be definite articles (e.g. in the star names) are indeed definite articles, then Romani gives a precedent for a degree of systematic variation in their form.

3. Another conjunction or particle?

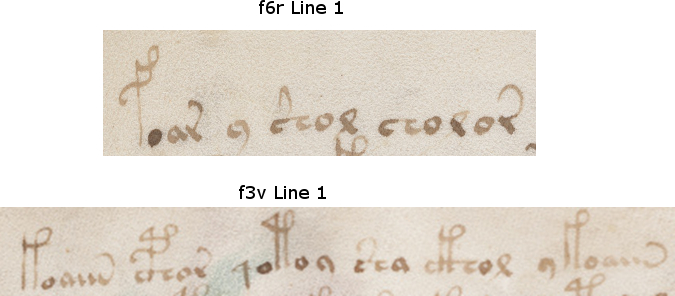

A third possible contender for a grammatical element can be seen here:

The second word in the first example (from Voynich f6r line one)Â is the sign which resembles a 9 (EVA:y). In the second example, from Voynich f3v line 1, we see the first word (EVA:koaiin)Â repeated later in the line, this time also with the 9 (EVA:y) in front of it Final Fantasy 10.

This second example is to my mind highly significant, since the chances of this word (EVA:koaiin) being repeated in the same line ‘accidentally’ are extremely slim. One reason for this is that the word itself is very rare in the manuscript, occurring in isolation only three times:

http://www.voynichese.com/#/exa:koaiin/0

Furthermore, with a prefix it is also very rare (6 occurences):

http://www.voynichese.com/#/exa:-koaiin/0

This makes it highly likely that the word is a lexical item (not a grammatical one), and possibly a noun. I have argued before that it is probably the name of the plant pictured in f3v. It further means that it is probable that the 9 symbol (EVA:y) in front of the second occurrence of the  word must be a grammatical or syntactic marker of some sort, a finding which we can state with unusual confidence. But what does it mean?

Derek Vogt recently posted an interesting discussion, suggesting that this particle, which might represent an /n/ sound (see my original 2014 article and Derek’s larger scheme) could be “something that goes between alternative names for the same thing, regardless of whether it’s attached or independent”. In other words he also sees it as a possible conjunction of some sort. He offers further examples of the same sign being used in an (apparently) similar way on folios 6r, 6v, and 17r:

^pawr n xaš hašar^

^kãwy n $wr hõokwr^

^twrwr ntwrhar^

(Transcription using Derek’s scheme)

If this is true, and we have some sort of conjunction expressed by the prefixed or detached sound /n/, then it would be useful to look for languages which use this kind of particle in this way.

I cannot find any examples of this in modern Romani dialects (which does not mean that they did not exist in the 15th century), but curiously, Romani does use a similar marker to indicate a negative. Matras (2002: 114) reports on a “negative particle na” in Romani and in fact in Indo-European languages this is not uncommon. Fortson, in his Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2011:148) gives the example of French:

“in the modern language, verbs are negated with a preceding ne (historically the true negator, from Latin non) and a following pas.”

This could mean that in the Voynich example above we are instead dealing with a negation of some sort 큰 아이콘 다운로드. However, I feel that a positive, additive meaning would more suitably fit the context, if we can find one!

What does all this mean?

I have offered the examples above to illustrate my wider point, namely that we will make more progress in our attempt to decode the Voynich script and language if we can identify and then try to elucidate elements of the grammar and syntax, and not limit attention to the vocabulary alone.  I hope my examples illustrate how we can start to do this, even if it is difficult.

What does it NOT mean?

In addition, I have offered some examples from Romani  to show how we might then try to match what we find in the VM with a known language. (It is curious that Derek has also recently identified some possible Romani words in other parts of the manuscript, see here.)

However, I feel it is important to emphasise that I am NOT arguing that the language of the VM is in fact a form of Romani. The evidence is simply too thin to make any such deductions at this stage.

I am sadly aware from past experience that some people in the Voynich community jump on the smallest statement, twist it, exaggerate it, and then misquote it to further their own agendas. (Previous experience has been compelling 🙂 in this respect.)

So let me state it loud and clear – I am not stating that the manuscript is written in Romani, merely that we should treat this as an interesting possibility and keep investigating it carefully and with an open mind to other possibilities.

References:

Fortson, B.  (2011) Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction John Wiley & Sons

Manchester University Romani site:Â http://romani.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/whatis/structure/nominals.shtml

Matras, Y Download Cain Abel. (2002) Romani A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press,

- Posted in: Voynich ♦ Voynich script and language

67 Comments