Voynich f6v: Ricinus communis, the Castor Oil plant?

In this full and detailed post I will discuss page f6v of the Voynich manuscript (VM), following the analytical approach and provisional findings which I set out in my Feb 2014 paper.  In summary, I will propose here that the plant depicted on that page can be identified with some confidence as Ricinus communis, also known as the Castor Oil plant, on the basis of analysis by a number of biologists. I will then offer evidence that the first word of that page, transcribed in the EVA transcription system as KOAR, can be read as ‘K A W R’ or similar, and possibly represents the name of the plant, perhaps deriving ultimately from the Arabic name for Ricinus communis, /xarwaÊ•/, roughly Kharwa’. I will then suggest that as such, it is consistent with, and supports, the analytical framework I set out in that earlier paper, and therefore represents a small but valuable step in the decoding.Â

In summary, I will propose here that the plant depicted on that page can be identified with some confidence as Ricinus communis, also known as the Castor Oil plant, on the basis of analysis by a number of biologists. I will then offer evidence that the first word of that page, transcribed in the EVA transcription system as KOAR, can be read as ‘K A W R’ or similar, and possibly represents the name of the plant, perhaps deriving ultimately from the Arabic name for Ricinus communis, /xarwaÊ•/, roughly Kharwa’. I will then suggest that as such, it is consistent with, and supports, the analytical framework I set out in that earlier paper, and therefore represents a small but valuable step in the decoding.Â

I will follow the approach set out in my Feb 2014 paper: in Step 1 I first examine the Voynich illustration in comparison  with mediaeval depictions and in the light of other, independent, scholars’ analysis of the illustration, so as to to examine the case for the identification. In Step 2 I then turn to discuss the possible plant name in relation to the first word of the Voynich page, drawing on mediaeval names for the plant in different languages.

However, before the discussion itself I want to acknowledge the contribution of the person who prepared a lot of the groundwork for this analysis and stimulated me to pursue it wms 다운로드.

Reddit:Â Shaun R.L. King

A main motivation for putting my paper in the public domain in Feb 2014 was to encourage others to evaluate, comment, modify and perhaps extend my approach and findings.  I participated in an open discussion on the internet site Reddit, and was contacted by Shaun R.L. King, using his Reddit username, who proposed an intriguing analysis over several mailings. With his permission I will repeat his comments here, and add numbers so I can discuss his analysis piece by piece below. Shaun writes:

1.  “I’ve been looking through the manuscript with my brother (a horticulturist) …….. We believe F6V is the Castor Oil Plant (Ricinus communis), which has been used in traditional herbal medicine from at least the Ancient Egyptian period. Petersen [and] Ethel Voynich …… have also classified it as the Castor Oil Plant.”

2. “Using your decoding of the letters so far, one can see that the first four letters of the first word on the page (F6V) can be transcribed into the Latin alphabet as koÉ™r (/k/ /o/ /É™/ /r/). The modern Arabic term for the Castor Oil Plant is خروع, transliterated into the Latin alphabet as Khrw or Khru. I believe this also supports your view that the approximate sound of the transcribed /a/ could be /wa/ wpf 테마 다운로드. This results in a proposed sounding of the word as Kawar.”

3. “I’m pretty sure the word in the text is longer than these sounds, but I can’t be sure due to the range in spacings throughout the manuscript.”

4. “Apart from Petersen ……. and Ethel Voynich’s claims that the plant in question is Ricinus Communis, the best source I have found to support the view would be an illustration of the plant by Matthaeus Platearius in his 12th century work on herbal medicines entitled Circa Instans/Liber de Simplici Medicina/Le Livre des simples medecines/The Book of Simple Medicines, which was based on the work of Dioscorides. …… illustrations associated with it are by the French artist Robinet Testard” [Link to the illustration reproduced below]

Click here to see a larger version of the image

During this exchange with Shaun, his analysis struck me as professional and plausible. I knew that the plant had been identified previously as Ricinus communis, as Shaun noted, and I had also wondered fleetingly about the first word. Shaun’s message set me off researching it in detail, for which I’m grateful.

I was also gratified that someone else had been able to follow the procedure proposed in my paper, and had made use also of the signs I had provisionally identified in a way which seemed to support my analysis.

After further research I now believe that Shaun (and his brother) have indeed made a potentially significant contribution – though of course the analysis must still be considered provisional and partial while we build up more evidence 야마토 게임 다운로드. Let me now offer the analysis in full, fleshing out what Shaun has suggested with further evidence and discussion.

Step 1. Identification of the plant

As Shaun noted, a number of Voynich scholars have identified this plant as Ricinus communis, including Peterson, and Ethel Voynich, supported also by Velinska. Recently another biologist from Finland (who wishes to remain anonymous) has also supported this identification. The historical evidence also seems compelling, as we can see when we can compare the Voynich picture (below left) with the picture produced in around 1500 probably by Robinet Testard.

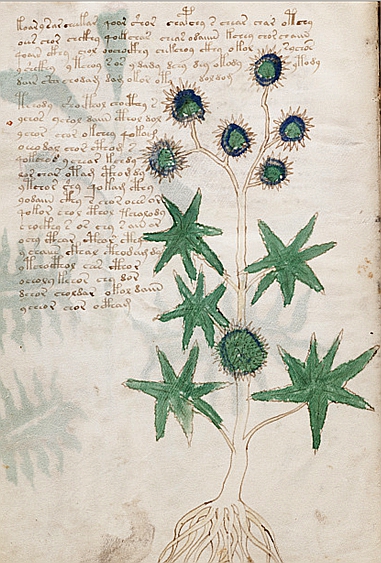

Left: VM f6v.       Right: Illumination, France, Robinet Testard (?), ca 1500. Illustration  of Palma Christ/Ricinus for Matthaeus Platearius, Le Livre des simples médecines. Fr 동굴이야기 다운로드. F. v. VI, 1. fol. 154 v, St. Petersburg, National Library

In this illustration we see (assuming aspects of ‘zooming’ on the part of the artist) “a representation of a rather stout plant with palmate leaves (i.e. lobes radiating from a single center) and with big, round, spiky fruits”, to quote the Finnish biologist. Even the colour appears similar to the Testard illustration.

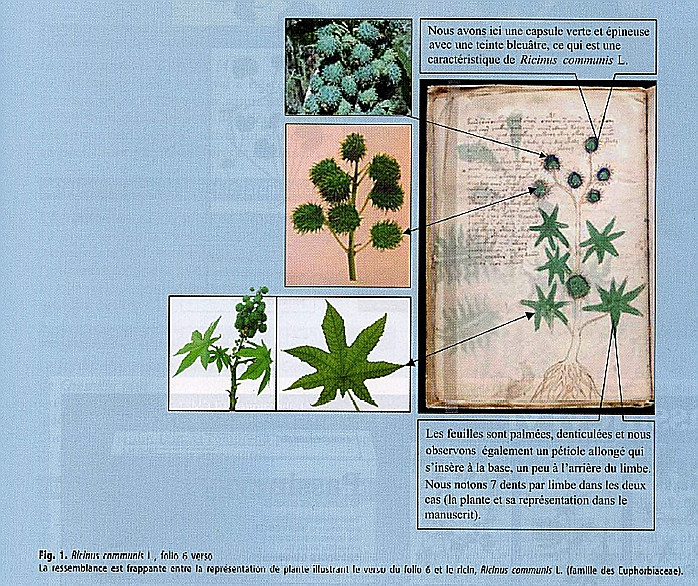

A further detailed analysis of this plant has been made by the French biologist Dr. Guy Mazars, President of the European Society of Ethnopharmacology, together with Christophe Wiart (Mazars & Wiart, 2006) . In their paper/interview they argue with detailed evidence that the plant is Ricinus communis, and we can reproduce part of that paper, with illustrations, here (translations are mine):

The caption at the top reads: “Nous avons ici une capsule verte et épineuse avec une teinte bleuâtre, ce qui est une caractéristique de Ricinus communis L.” (“Here we have a green spiny capsule with a bluish tint, which is characteristic of Ricinus communis L.)

The caption at the bottom reads: “Les feuilles sont palmées, denticulées et nous observons également un pétiole allongé qui s’insère à la base, un peu à l’arrière du limbe. Nous notons 7 dents par limbe dans les deux cas (la plante et sa représentation dans le manuscrit).” ( “The leaves are palmate, serrated and we also observe an elongated petiole joining the leaf at its base, a little behind the leaf edge. We note 7 teeth per blade in both cases, i.e. in both the plant and its representation in the manuscript”).

It is difficult on the basis of this accumulation of evidence and detailed analysis, from these authors and other plant specialists, to disagree with their conclusion as expressed below the illustration, that “La ressemblance est frappante entre la représentation de plante illustrant le verso du folio 6 et le ricin, Ricinus communis L (famille des Euphorbiaceae).”  (“The resemblance between the plant illustrated in folio 6v and ricin, Ricinus communis L ( Euphorbiaceae family) is striking”) Demigat download.

In summary, the evidence therefore seems to me compelling that the Voynich plant can be identified with some confidence as Ricinus communis, the castor plant, used for centuries and still in use today for a variety of medicinal uses.

Step 2. Plant name

In his message cited above, Shaun King noted that the Arabic name for this plant is  خروع, /xarwaÊ•/ or /xirwaÊ•/, written with four Arabic letters and transcribed as approximately ‘kh  i/a/u  r  w a ‘. It is useful, as preparation for the discussion which follows, to explain the Arabic name in brief:

-The first letter is the the guttural /x/ sound as in the Scottish word ‘loch’.

-The second letter is the consonant /r/.

-The short vowel between the two (approximately /É™/ or /i/) is usually omitted in unvowelled writing, in a way typical of ‘abjab’ scripts, and must be supplied by the reader from memory.

-The third letter is known as ‘waw’ and can either be a long vowel similar to ‘oo’, or can be a /w/ sound. Here it is read as the latter, and the reader must also supply a following /a/ vowel.

-The final letter is the throaty guttural consonant known as ‘ayn’ (Ê•)Â which does not exist in most European languages. (It is the same sound as I mentioned in my Feb 2014 paper as the start of the word transcribed as ‘arar’, juniper) 크롬 웹사이트 다운로드. When Arabic words containing this sound are borrowed into other languages, including even the word ‘Arabic’ itself, this sound is often written as ‘a’, or omitted.

An interesting and detailed account of the history and the name can be found in Dymock, whom it is worth quoting at some length:

“In the proverbial language of the Indians the Castor plant is emblematic of frailty; they say:—Naukri a rand ki jar hai (service is like the root of the Castor plant). The Arabs appear to have first become acquainted with the tree in India, as they call the seeds Simsim-el-hindi, “Indian Sesamum,” and the plant Khirvaa [Dymock insertes the Arabic word ‘Kharwa’ here] , a word which signifies any weak or frail plant; the properties they attribute to it are also those mentioned by Sanskrit writers. Again, in the Saptasaaka of Hála, we find the large and swelling breasts of the peasant girl likened to the Eranda leaf, and in Arabic we have the expression [Dymock inserts the phrase ‘imra’at kharw’a’ here, meaning ‘fragile girl’] applied to a beautiful and tender girl.

R. communis is the Bidanjir and Kinnatu of the Persians ; it also bears various local names, such as Gerchak in the Shahpur District, and Buzanjir, “goat’s fig,” in Khorasan.” (Dymock 1893: 302)

Dymock goes on to note that Herodotus called the plant ‘Kiki’, Theophrastus called it ‘Kroton’, it is mentioned in Pliny, and in Hebrew it is ‘kikajon’.

It is noteworthy that Dymock himself, even though he inserted the correct Arabic script into his text, transcribed it wrongly as ‘Khirvaa’, transmuting the original Arabic ‘waw’ (/w/)into a /v/, and the final ‘ayin’ as the long vowels ‘aa’ one note. This was probably because he was reading it through an Indian/Persian prism, and this demonstrates how easily the original consonants could be altered.

Below that, Dymock also mentions an alternative name, “Gerchak“.  This probably derives from the Persian ‘kerchak’  ( كرچك ) (Urn, T and T.Kwee Lim 2012:487), which is probably the source for the similar modern Armenian word Gerch’ak (Ô³Õ¥Ö€Õ¹Õ¡Õ¯). All of these most probably derive in part from the initial element of the Arabic word, the ‘Khir’ transforming to ‘Ker’ and ‘Ger’, with the addition of a Persian suffix ‘chak’ – although I am not aware of what this suffix might mean.

In his comprehensive 15th century Pharmacological manual ‘Useless for Ignoramuses’ the Armenian scholar and physician Amirdovlat, whom I discuss at length elsewhere, lists the plant Ricinus communis in a number of places, most frequently in a version which can be transcribed as ‘Kharvay’ (Vardanian, 1990: item 857), again clearly showing Persian influence and again transmuting the Arabic /w/ to Persian /v/ and the final Arabic consonant into a vowel/diphthong. (Curiously, Amirdovlat does not include a version resembling modern Armenian Gerch’ak, suggesting that that term was adopted from Persian after the 15th century.)

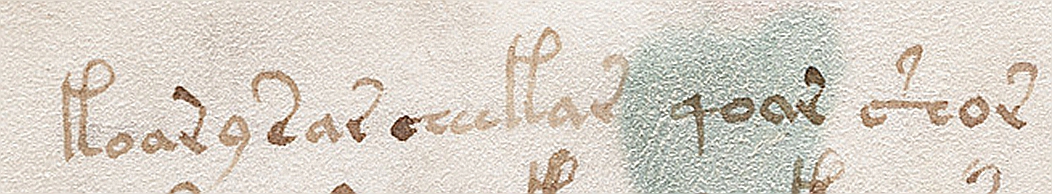

If we return now to the Voynich manuscript, I argued in my Feb 2014 paper that in terms of methodology we should look initially for the plant name in the first word of the page, following common mediaeval herbal practice Jokerost. In this case the first few words on page 6v are the following:

Shaun King, in his correspondence cited above (point 4) noted the difficulty of identifying spacing in this line, so it is most secure to follow Takahashi’s transcription, which for the above segment of line 1 is set out as six words:

koar y sar oheekar qoar Shor

Following the provisional decoding set out in my Feb 2014 paper, the first word, transcribed by Takahashi as ‘koar’  should be read /k a ə r/ or alternatively as /k a w a r/. As Shaun King suggests, it is indeed plausible to see this as related to, and deriving from, the original Arabic word, assuming the same kind of consonant alteration as we saw in the Persian, Armenian and Indian versions. (The placing of a possible /w/ before the /r/ could be an example of metathesis, a common occurence in lexical borrowing across languages, in this case transforming Arabic ‘k(h)irwa’ into ‘kiwar’.)

In other words, it appears that we have on this page a convincing identification of the plant illustrated, and an historically and linguistically plausible identification of the first word of that page as a credible name for that plant, which would appear to derive, as in the case of a number of other languages, from the original Arabic name.

(A further point of interest is the fifth word, transcribed as ‘qoar’. Given that mediaeval herbal books often began the page by listing variants of the plant name in other languages, it is possible that this is a variant of ‘kawar’, perhaps to be read as ‘gawar’ or with a  guttural sound resembling ‘q’ = ‘qawar’. This is speculative, but could be corroborated by analysis of further names and sounds.)

Summary

In summary, it is suggested that the plant on this page can be confidently identified as Ricinus communis. It is then provisionally proposed that the the first word of that same page could well be the plant name, and that it can be tentatively read, using the signs I identified previously, as /kawar/ or /k a ə r/ consistent with the well-known and widely diffused Arabic plant name for Ricinus communis dubbing of the theater version.

In more informal terms – this longer analysis seem to support in full the analysis offered by Shaun King in his original correspondence, and once again I am grateful to him for his work.

Of course, despite the evidence given here, and as with all the plant identifications made in my Feb 2014 paper, this analysis on its own must be considered speculative. However, when taken together with the other analyses offered in that earlier paper, it appears both to fit well with the readings offered for other letters and words in the Voynich manuscript, and also to support the analytical scheme and its tentative identifications.

In short, it appears to be another small but positive step in the long road towards decoding and deciphering the script and language of the Voynich manuscript as a whole.

References:

Dymock, W. (1893) Pharmacographia Indica, a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India PART VI, London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Available at: Â https://archive.org/details/pharmacographia03dymogoog

Mazars, G show 프로그램 다운로드. & C. Wiartz (2006) Interview : L’Herbier du Manuscrit Voynich. Une pharmacopée d’origine asiatique, Phytothérapie (2006) Numérol.3, p.202-204 From: http://www.agem-ethnomedizin.de/download/Mazars-Goetz-Interview_Manu_Voynich.pdf AccessedÂ

Urn, T and T.Kwee Lim (2012) Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants, Volume 2, Springer, Accessed at: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4MDEqFGeKVoC&dq   16/3/2014

Vardanyan, S. (translator and editor) (1990) Nauchnoe nasledstvo (by Amirdovlat Amasiatsi) Tom 13, Nenuzhnoe dlia neuchei. Amirdovlat Amasiatsi, Nauka, 1990. ISBN 5020040320

- Posted in: Voynich plants

12 Comments